Automated Rewards via LLM-Generated Progress Functions

Vishnu Sarukkai, Brennan Shacklett, Zander Majercik, Kush Bhatia, Christopher Ré, Kayvon Fatahalian

Reward engineering is a major bottleneck when tackling sparse-reward RL tasks. We introduce ProgressCounts, a LLM-based automated reward engineering approach that achieves state-of-the-art performance while using 20x fewer samples than Eureka, the prior SOTA.

Our core insight is to decompose reward generation into two steps: 1) using LLMs to extract task-specific features from the current state, and 2) converting these features into rewards for learning. We extract task-specific features via progress functions, and we convert the output of progress functions into rewards via count-based intrinsic rewards.

Reward engineering is tedious

Consider the task of using two hands to grab the handles of a cup and swing it to a desired goal rotation.

To solve this type of task, researchers have historically used manually designed complex reward functions to provide dense signal for training effective policies:

right_hand_finger_dist = ...

left_hand_finger_dist = ...

quat_diff = quat_mul(object_rot, quat_conjugate(target_rot))

rot_dist = 2.0 * torch.asin(torch.clamp(torch.norm(quat_diff[:, 0:3], p=2, dim=-1), max=1.0))

rot_rew = 1.0/(torch.abs(rot_dist) + rot_eps) * rot_reward_scale - 1

up_rew = torch.zeros_like(rot_rew)

up_rew = torch.where(right_hand_finger_dist < 0.4,

torch.where(left_hand_finger_dist < 0.4,

rot_rew, up_rew), up_rew)

reward = - right_hand_finger_dist - left_hand_finger_dist + up_rew

Human reward design requires domain knowledge (ex. to swing the cup to the goal rotation, we should aim to minimize hand distance to cup, then cup distance to goal).

Human reward design also requires humans to weight and rescale reward terms (applying an inverse scaling to rotational distance in order to obtain the rotational component of the reward, setting up_rew to zero unless both hands are within distance 0.4 of the cup, etc.)

The process of designing these reward functions is often iterative, tedious, and brittle.

We aim to minimize the human effort required for reward generation.

Without scaffolding, LLM-based reward function generation is inefficient

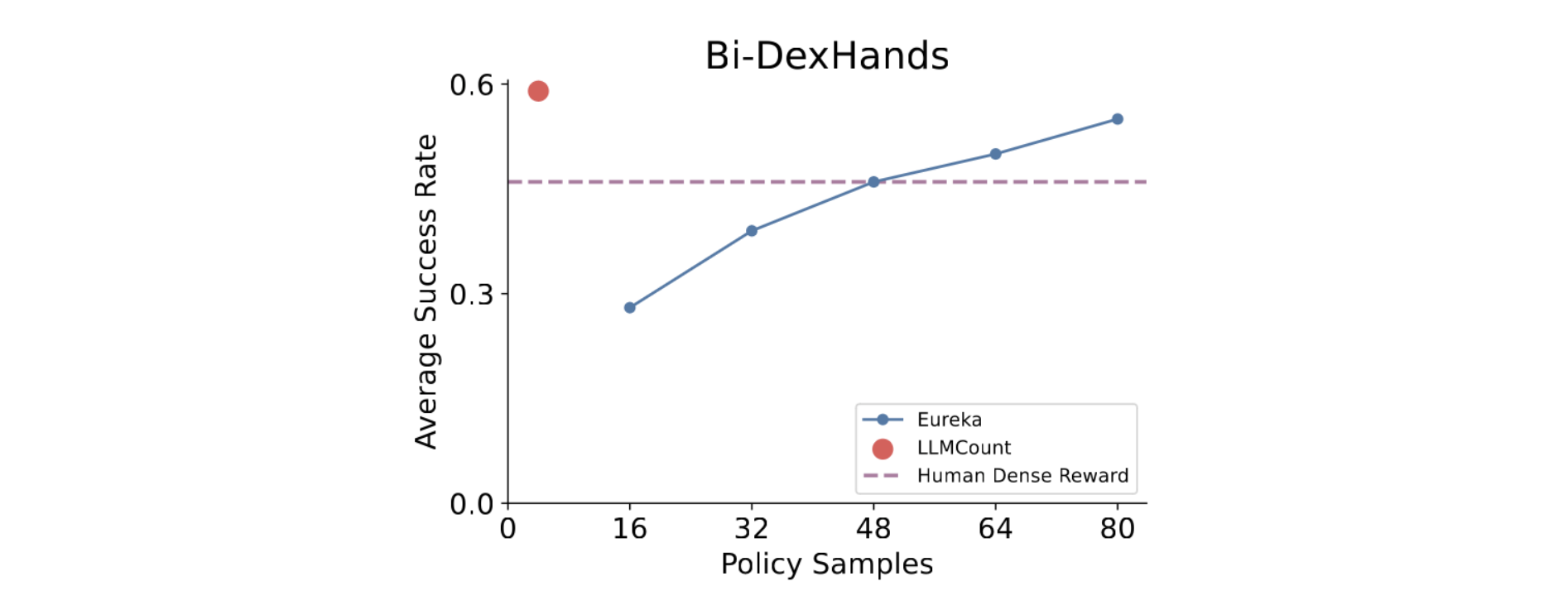

Enter large language models (LLMs), which have shown the potential to automate a variety of tasks. Prior work Eureka automates reward generation by providing task simulator code directly to an LLM, and having it generate a dense reward function for the desired task. While this direct approach to generating reward functions is appealing for its simplicity, it is empirically very inefficient–on the Bi-Dexhands benchmark, Eureka generates 48 candidate reward functions to find one that is on par with a human-written reward function, and writes 80 candidate functions to achieve its SOTA perfornamce.

LLMs consistently generate good hypotheses on the elements of the feature space that should be involved in the reward, but struggle with the reliable assembly of available environment features into effective rewards. Therefore, we structure the process of LLM-based reward function automation in order to improve its sample efficiency. First, we extracting task-specific features from the current state via LLM-generated progress functions that map task-specific states to generic features measuring task progress. Then, we convert these generic features into count-based intrinsic rewards for learning.

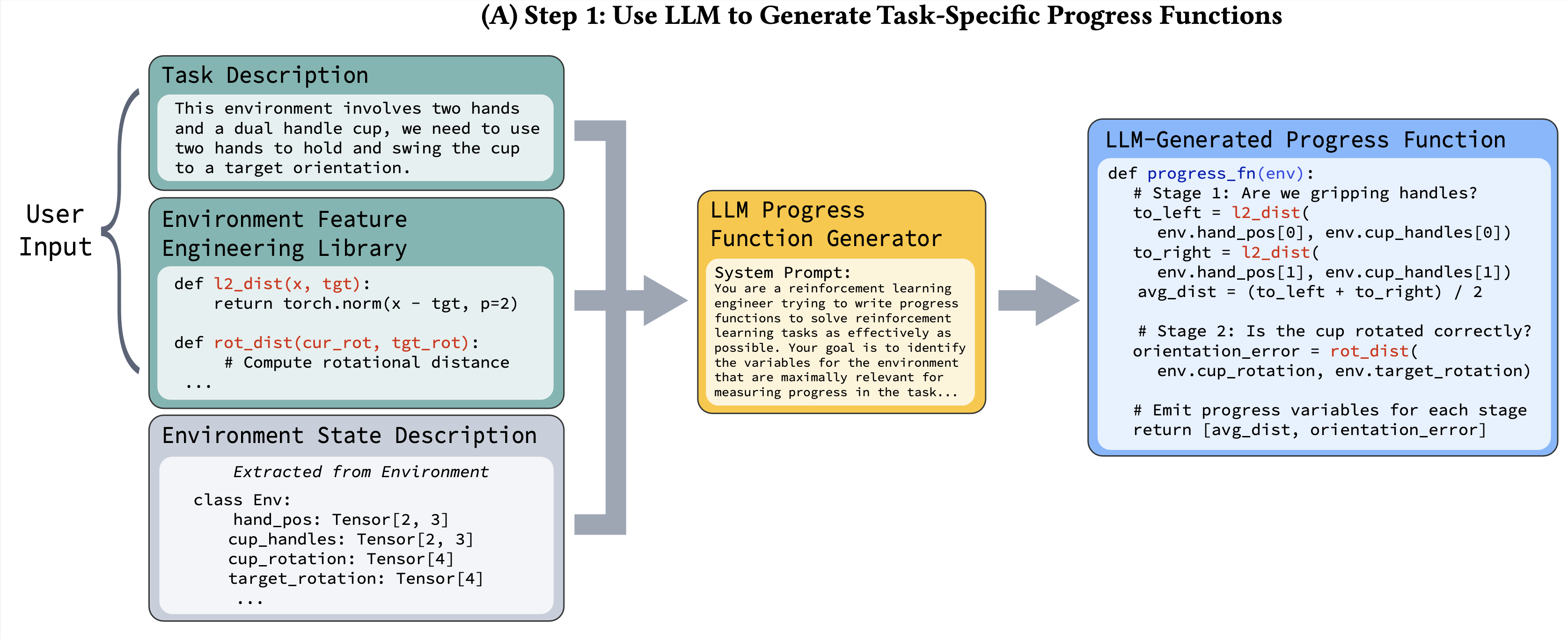

Progress functions: LLM task knowledge for feature extraction

Given a new task description, the first step of our process is to generate a progress function $P : S → R_k$, which takes environment features $s ∈ S$ as input, and outputs information about the current progress of the agent on the task. Especially for more complex tasks, it may be difficult to distill a task to a single feature that tracks overall progress. Therefore, a progress function, given a state, is asked to emit a positive scalar measure of progress for one or more subtasks. For instance, for the SwingCup task, which involves 1) gripping the handles of the cup, 2) rotating the cup to the correct orientation, a good progress function would break the task into two sub-tasks and return scalars measuring progress for both sub-tasks.

Specifically, the progress function outputs $[x_1,x_2,…x_k]$ where $x_i ∈ R$ tracks task progress for sub-task $i$. It also outputs additional variables $[y_1 , y_2 , …y_k]$ that inform our framework whether the progress variables xi are increasing or decreasing.

In order to generate progress functions, we provide the LLM with 1) function inputs: a description of the features in the environment state, 2) function outputs: the desired output of the progress function via a short task description, and 3) function logic: we structure the process of translating feature inputs to progress output by providing the LLM with access to a environment feature engineering library. These task inputs are standard in the literature.

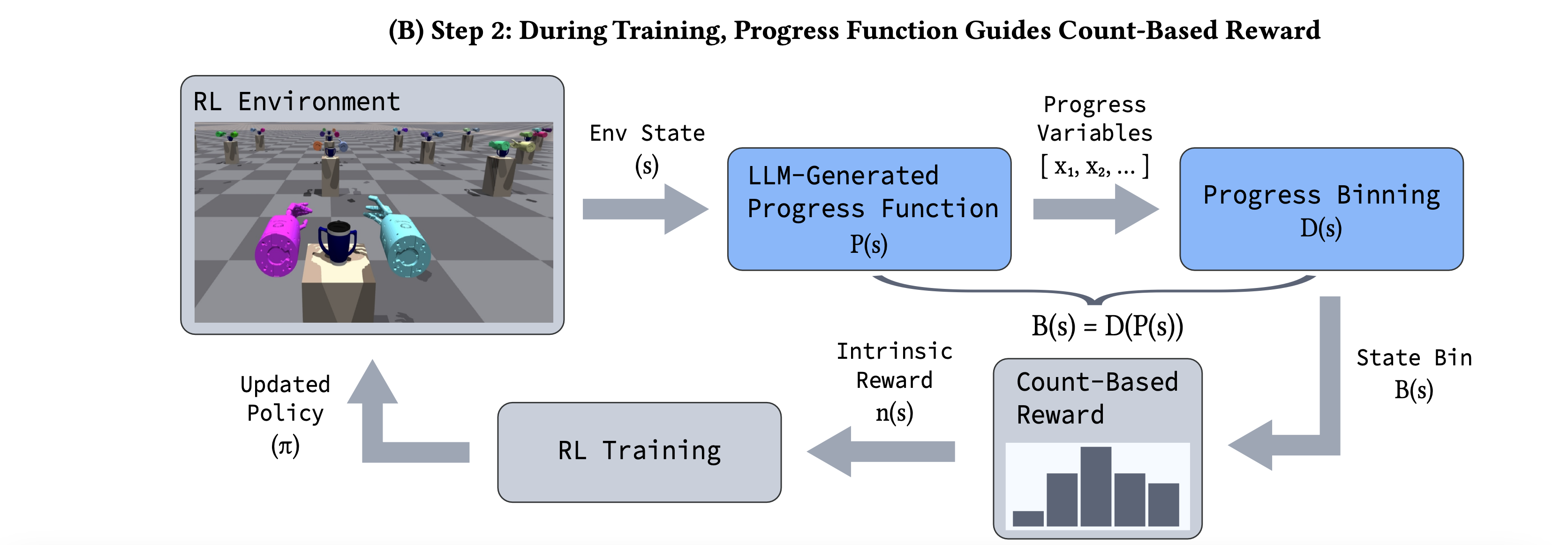

From progress to rewards: count-based intrinsic motivation

Given a perfect estimate of task progress, it may seem natural to directly use progress as a dense reward: for a given state $s$, compute the sum of the progress outputs $R_{sum} = \sum_i x_i$, and use progress sum $R_{sum}$ as the reward for reaching s. However, learning from dense rewards can be brittle–small mistakes in reward design often lead to a failure to learn effective policies. Progress functions offer highly simplified state representations—and given the coarse nature of these representations, we look for a more forgiving mechanism to generate rewards from these simplified representations. Therefore, we use a count-based intrinsic reward approach inspired by prior work that achieves state-of-the-art performance with domain-specific discretizations. We compute state visitation counts from progress features, and our count-based framework provides rewards when the policy reaches a rarely-visited state, implying that it has made new progress in solving the task.

A major leap in efficiency

Compared to Eureka, which requires many iterations of trial and error to find a good reward function, ProgressCounts drastically reduces the number of training runs. In fact, it only needs 20x fewer reward function samples than Eureka to achieve 4% better policy performance than Eureka. The framework was tested on the Bi-DexHands benchmark, a set of 20 bimanual manipulation tasks.

We find that both components of our algorithm–progress functions and count-based rewards–serve important roles in the efficiency and task performance of ProgressCounts. We also find that ProgressCounts is robust to choices of hyperparameters. Please see our paper for further experiments and details.

Why this matters

ProgressCounts offers the promise of shifting how we approach reward engineering. The progress-and-counts framework makes LLM-based reward generation efficient, opening the door for more effective automation in settings which can benefit from reinforcement learning when solving a large number of tasks.

Posts

-

Building Self-Improving LLM Agents: Paths Toward Lifelong Learning

Blog post authored jointly by Vishnu Sarukkai and Genghan Zhang

-

Diffusion Models and Policy Gradients Share a Common Structure

“True enough, this compass does not point north…It points to the thing you want most in this world.” – Jack Sparrow.

subscribe via RSS